Where Do Most Homeless People Live? Real Numbers Behind Shelter Use and Street Living

Dec, 5 2025

Dec, 5 2025

Homelessness Situation Calculator

Based on 2025 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development data

0

in shelters (35% of total)

Alternative living situations:

0

not in shelters

Breakdown of alternative housing:

- Cars & vans 0

- Couch surfing 0

- Abandoned buildings 0

- Other outdoor spaces 0

- Transitional housing 0

Why this matters

Most shelters don't have enough space for everyone. Only 35% of homeless people stay in shelters on any given night. The rest are living in cars, doubled up with friends, or abandoned buildings. This invisible homelessness affects millions of people who don't get counted in traditional statistics.

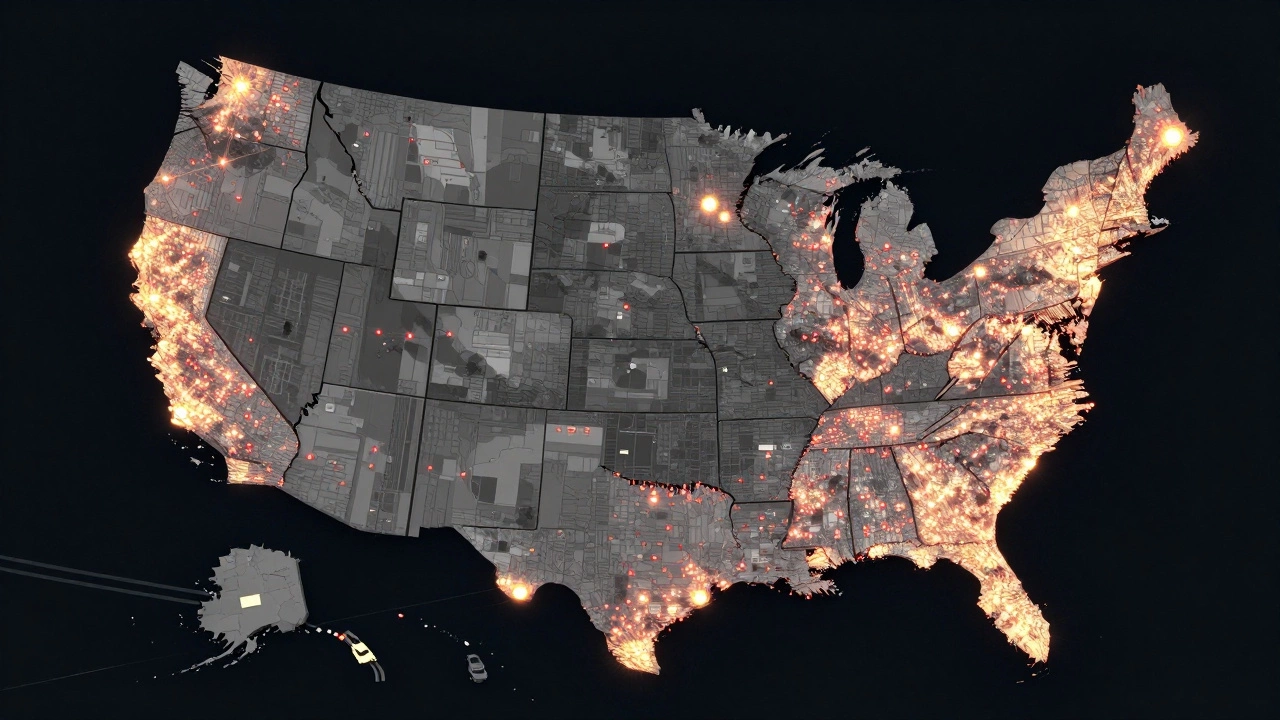

When you think of where homeless people live, you might picture rows of beds in a shelter or someone sleeping under a bridge. But the truth is more complicated-and more widespread-than most people realize. In 2025, over 120,000 people in the U.S. were counted as homeless on any given night, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. That’s more than the population of cities like Boise or Tulsa. And where do most of them actually live? Not in shelters. Not in tents. Not even on sidewalks. The majority are living in places most of us never see: cars, abandoned buildings, couches with friends, and overcrowded apartments.

Most homeless people aren’t in shelters

It’s a common myth that homeless shelters are the main solution. In reality, only about 35% of homeless people stay in shelters on any given night. That means more than two out of every three people experiencing homelessness are sleeping somewhere else. Why? Shelters are full, far too few, or not safe for certain groups. Many shelters have strict rules-no couples, no pets, no drugs, no staying past 7 a.m. For someone fleeing abuse, dealing with mental illness, or just trying to hold onto dignity, those rules can make shelters worse than the streets.

In cities like Los Angeles, New York, and Seattle, shelter waitlists can stretch for weeks. Some people give up and choose to sleep in their cars. Others stay with friends, moving from one couch to another. This is called "doubling up," and it’s the fastest-growing form of homelessness in America. The National Alliance to End Homelessness reports that over 40% of homeless families are living this way-crammed into someone else’s living room, kitchen, or basement. They’re not on the streets, but they’re not safe or stable either.

Where do homeless people sleep when they’re not in shelters?

Here’s where the real picture comes into focus:

- Cars and vans: About 20% of homeless individuals sleep in vehicles. In California, this number is closer to 30%. People park near Walmart lots, church parking lots, or quiet side streets. Some keep a change of clothes, a cooler of water, and a phone charger in the back seat.

- Couch surfing: As mentioned, over 40% of homeless families and nearly 25% of single adults rely on temporary stays with friends or family. This is invisible homelessness-no one sees it, no one counts it, but it’s real.

- Abandoned buildings: In cities with old industrial areas, like Detroit or Philadelphia, people move into empty factories, warehouses, or boarded-up homes. These places are dangerous-no heat, no running water, risk of collapse-but they’re free.

- Outdoor spaces: Parks, under bridges, and along riverbanks still hold a portion of the homeless population. In winter, this number drops as people seek any kind of cover. In summer, it rises again.

- Transitional housing: A small group-about 10%-live in government-funded transitional housing programs. These are temporary apartments with case managers, but they often have long waiting lists and strict eligibility rules.

The point isn’t that shelters don’t matter-they do. But they’re not the main answer. The real issue is the lack of affordable housing. A person working full time at minimum wage in most U.S. states can’t afford a one-bedroom apartment. Rent has gone up 40% since 2019, while wages barely moved. That gap is what’s pushing people out of homes and into cars, couches, and streets.

Big cities have the most visible homelessness, but rural areas are growing fast

You hear about homelessness in New York, San Francisco, or Los Angeles. Those cities have the highest raw numbers. But per capita, some of the worst situations are in smaller cities and rural areas. Places like Anchorage, Alaska, or rural counties in Georgia and Alabama have seen homelessness rise faster than any major city.

Why? Rural areas have almost no shelters. There’s no public transit. No food banks within walking distance. No social services. If you lose your job or get evicted in rural Mississippi, you don’t have a shelter down the street. You either stay with relatives, sleep in your truck, or leave town. And if you’re sick, disabled, or dealing with trauma? There’s nowhere to turn.

In 2024, a study by the Urban Institute found that rural homelessness grew by 27% in five years-more than double the rate in urban areas. Yet rural communities get less than 5% of federal homeless funding. The system is built for cities. It ignores the quiet crisis happening in towns with populations under 10,000.

Who are the people living in cars and couches?

Homelessness isn’t just one kind of person. It’s a mix of families, veterans, teens, seniors, and people with disabilities.

- Families with children: One in three homeless people is part of a family. Many are single mothers working two jobs, still unable to afford rent after childcare and bills.

- Youth: Over 400,000 young people under 25 experience homelessness each year. Many are kicked out for being LGBTQ+, or they age out of foster care with no support.

- Seniors: People over 55 are the fastest-growing group of homeless individuals. Fixed incomes, medical bills, and rising rent have pushed retirees into their cars.

- Veterans: While veteran homelessness has dropped since 2010, over 33,000 still sleep without a home on any given night. Many struggle with PTSD, lack of job skills, or no family to turn to.

There’s no single profile. There’s no "typical" homeless person. There’s just a system that fails too many people too often.

Why don’t more people go to shelters?

Shelters aren’t the problem-our approach to homelessness is.

Most shelters are designed for single men. They’re often crowded, noisy, and unsafe for women, LGBTQ+ people, or anyone with trauma. Many require sobriety-meaning someone with an addiction can’t get help until they’re clean. But how do you get clean without a safe place to sleep? It’s a loop no one talks about.

Also, shelters are temporary. You can’t store your stuff. You can’t bring your dog. You can’t stay past morning. For someone trying to find a job, go to court, or attend therapy, that’s not enough. They need stability, not a bed for eight hours.

Some cities are trying new models. Places like Salt Lake City and Houston have shifted to "Housing First"-giving people permanent apartments without requiring sobriety or job readiness first. Results? Homelessness dropped by 50% in ten years. But most cities still cling to old models: clean up, get sober, get a job, then get housing. It doesn’t work. People need housing first. Everything else comes after.

What’s really behind the numbers?

Homelessness isn’t caused by laziness or bad choices. It’s caused by broken systems.

Here’s what’s really happening:

- Rent is too high: In 37 states, a person working 40 hours a week at minimum wage can’t afford a two-bedroom apartment.

- Wages haven’t kept up: Since 1978, rent has gone up 165%. Wages? Up 18%.

- Public housing is shrinking: There are only 5 million public housing units for 21 million low-income households.

- Mental health care is inaccessible: Half of all homeless adults have a mental illness. Few have access to treatment.

- Evictions are rising: Over 2 million evictions happen each year in the U.S. Most are for rent that’s just $200 overdue.

These aren’t random tragedies. They’re the result of policy choices. We’ve cut funding for housing, mental health, and social services for decades. Now we’re surprised when people end up sleeping in cars.

What’s being done-and what actually works?

Some cities are changing. In 2023, Austin, Texas, opened its first permanent supportive housing complex for people who’d been homeless for over ten years. No strings attached. Just a door, a bed, and access to a nurse and case manager. Within six months, 82% of residents were still housed. That’s the model that works.

Other cities are trying tiny home villages-simple, safe, warm units with shared bathrooms and kitchens. In Portland and Seattle, these villages have cut street homelessness by 30% in two years. They’re not perfect. But they’re better than tents under bridges.

And then there’s the simplest fix: rent control. In cities that passed rent stabilization laws, homelessness rose slower. In places that didn’t, it exploded.

The truth is, we know how to fix this. We’ve done it before. In the 1980s, the U.S. cut funding for affordable housing and mental health services. We didn’t fix homelessness-we just moved it from hospitals to streets.

Now we have the data. We have the solutions. What we’re missing is the will to act.

Do homeless shelters have enough space for everyone?

No. On any given night, there are only enough shelter beds to house about one-third of the homeless population. In big cities like Los Angeles and New York, waitlists can be weeks long. Many shelters also have restrictions-no couples, no pets, no staying past morning-that make them unusable for large groups or people with trauma.

Are most homeless people living on the streets?

No. Only about 25% of homeless people sleep outdoors. The majority live in cars, doubled up with friends or family, or in abandoned buildings. Street homelessness is the most visible form, but it’s not the most common.

Why don’t homeless people just get a job?

Many do work. In fact, 40% of homeless adults have at least one job. But minimum wage doesn’t cover rent in most places. A person working full time at $15/hour earns $31,200 a year. The average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in the U.S. is $1,800 a month-that’s $21,600 a year. After taxes, food, transportation, and healthcare, there’s nothing left for rent.

Is homelessness only a problem in big cities?

No. While big cities have the highest numbers, rural areas are seeing the fastest growth. Small towns often have no shelters, no public transit, and no services. A person who loses their home in rural Alabama might have to drive 50 miles to find help-or sleep in their truck.

What’s the most effective way to reduce homelessness?

The most proven method is Housing First-giving people permanent housing without requiring sobriety or job readiness first. Cities like Houston and Salt Lake City cut homelessness by half using this model. It works because stability comes before recovery. You can’t fix mental health or find a job if you’re sleeping in a car.