What Were Social Clubs Used For? A Real History of Why People Joined

Feb, 13 2026

Feb, 13 2026

Back in the 1800s and early 1900s, if you walked down a city street in London, New York, or Melbourne, you’d see men-sometimes women-heading into small buildings with painted signs: Working Men’s Club, Ladies’ Literary Society, Odd Fellows Lodge. These weren’t bars, libraries, or churches. They were social clubs. And they weren’t just for hanging out. They were lifelines.

They Gave People a Place to Belong

In a time before smartphones, public parks, or even reliable public transportation, people didn’t have many ways to connect outside of family or work. Social clubs filled that gap. For factory workers, clerks, teachers, and even shopkeepers, a club was one of the few places where you could be around others who understood your daily grind. You didn’t need money to join-just a willingness to show up. In return, you got a seat, a cup of tea, and someone who’d listen when you had a bad day.

These weren’t fancy places. Many started in rented rooms above a butcher shop or in the back of a pub. But they had rules. Attendance. Dues. Voting. And that structure mattered. It gave people a sense of order in a world that often felt chaotic. A club wasn’t just a room. It was a promise: you belong here.

They Provided Real Financial Support

Think of social clubs as early versions of insurance. If you got sick, lost your job, or died, your club often paid out. In 1870s England, a typical working men’s club might collect a few pence a week from each member. That pooled money became a safety net. If a member broke a leg on the job, the club paid for a doctor. If a worker died, his family got a funeral grant. Some clubs even had sick pay-cash handed out weekly while you recovered.

This wasn’t charity. It was mutual aid. You paid in, you got back. No government program. No corporate policy. Just people helping each other. By the 1920s, over half of British working-class men belonged to a club with some kind of financial backup. In Australia, similar groups formed among miners and dockworkers. These weren’t hobbies-they were survival tools.

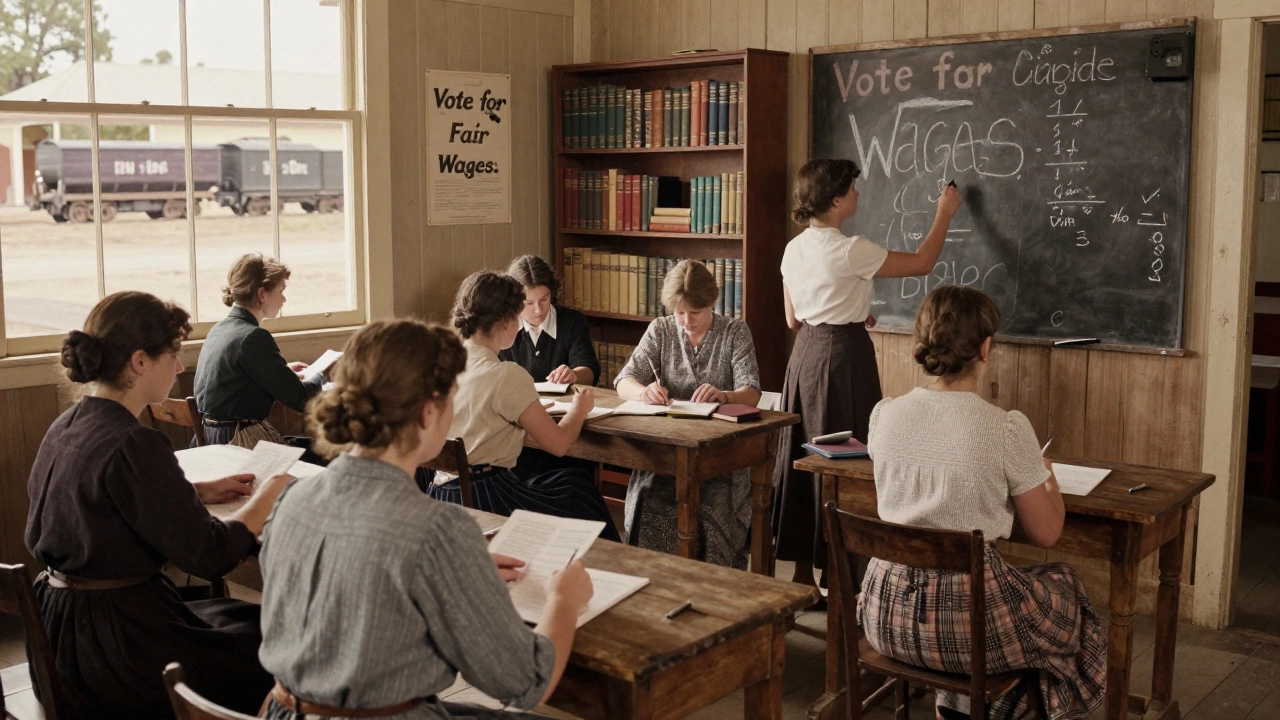

They Were Political and Educational Hubs

Many clubs doubled as classrooms. You could attend a lecture on anatomy, learn how to write a letter, or debate whether the government should raise wages. In Philadelphia, the Workingmen’s Institute had a library with 12,000 books. In Melbourne, the Victorian Socialist Club hosted weekly talks on labor rights. Women’s clubs were especially active in this space. The Ladies’ Social and Educational Association in Adelaide ran literacy classes for factory workers as early as 1891.

These weren’t just about reading. They were about power. If you didn’t have a university degree or political connections, a club gave you a voice. Members wrote petitions, organized strikes, and even ran for local office. One club in Liverpool helped elect its own president to the city council in 1903. That kind of influence didn’t come from wealth. It came from organization.

They Offered Recreation When There Wasn’t Much Else

Before TV, radio, or cheap movies, entertainment was scarce. Social clubs offered music, games, and dance. Chess tournaments. Choirs. Boxing matches. Even poetry readings. In Wales, coal miners’ clubs held annual eisteddfodau-Welsh-language poetry and music festivals. In New York, Irish immigrant clubs hosted ceilidhs. In Australia, Italian and Greek communities used clubs to keep traditions alive.

These weren’t just fun. They were identity. For immigrants, clubs were where you didn’t have to explain your accent or hide your food. For women, especially in rural areas, a club was one of the few places they could leave the house without a chaperone. A weekly dance wasn’t frivolous-it was freedom.

They Built Trust in a World Without Institutions

Back then, banks were risky. Police were often corrupt. Government services were slow or nonexistent. So people trusted their club more than any official body. Your club knew your name. Your family. Your troubles. It didn’t ask for paperwork. It just helped.

When a member’s house burned down, the club raised money. When a child needed a school uniform, the club bought it. When a widow couldn’t afford rent, the club found her a room. These weren’t big gestures. They were quiet, regular acts of care. And that consistency built something rare: real trust.

Why Did They Decline?

By the 1950s, things started to change. The government began offering unemployment benefits, pensions, and public libraries. TV brought entertainment into homes. Cars made it easier to travel. People didn’t need to rely on their neighbors as much.

Many clubs closed. Others became bars. Some turned into private gyms. The ones that survived did so by adapting-adding bingo nights, hosting wedding receptions, or becoming community centers. But the original purpose? The mutual aid? The shared power? That faded.

Today, you’ll still find a few left. A working men’s club in Sheffield. A women’s reading circle in Hobart. A Filipino association in Melbourne that still collects dues to help new arrivals. They’re rare. But they’re still there. And they still do what they always did: make people feel like they matter.

What Was Really at Stake?

Social clubs weren’t about hobbies. They weren’t about status. They were about dignity. In a world that treated workers as replaceable, clubs said: you are not alone. You are not invisible. You are part of something.

That’s why they mattered. Not because they were perfect. But because they were real. And in a time when so little was guaranteed, they were one thing you could count on.

Were social clubs only for men?

No. While many early clubs were male-only, women formed their own clubs from the 1800s onward. In Britain, the Women’s Social and Political Union started as a club before becoming a suffrage movement. In Australia, women’s clubs ran libraries, hosted childcare, and raised money for hospitals. Some clubs were mixed, especially in immigrant communities. By the 1920s, over 40% of club members in major cities were women.

Did social clubs have anything to do with religion?

Sometimes, but rarely as a primary purpose. Some clubs were started by churches, like Methodist temperance societies. Others were explicitly secular. The key difference was that clubs didn’t require religious belief to join. You didn’t have to pray. You didn’t have to attend services. You just had to pay your dues and show up. Many clubs kept religion out on purpose-so they could include Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and atheists all in one room.

How did social clubs differ from modern gyms or bars?

Modern gyms sell fitness. Bars sell drinks. Social clubs sold belonging. They had rules, voting, and shared responsibilities. Members didn’t just pay for access-they helped run the place. Many clubs owned their buildings. They hired staff. They made decisions together. There was no corporate owner. No franchise model. Just a group of people who decided they’d look out for each other. That’s why they lasted decades, even when money was tight.

Are there any social clubs left today?

Yes-but they’re rare. The Oldham Working Men’s Club in England still holds weekly meetings and pays out emergency grants. In Melbourne, the Italian Australian Social Club supports new immigrants with language help and housing referrals. A few rural clubs in Wales and Scotland still run bingo nights and funeral funds. Most have adapted, but the core idea remains: mutual support, not profit.

Why did immigrant communities rely so heavily on social clubs?

Because they were often shut out of mainstream institutions. Banks refused loans. Employers didn’t hire them. Local governments ignored them. Clubs became their government, their bank, their hospital, and their family. A Greek club in Sydney didn’t just host dances-it helped new arrivals find jobs, translate documents, and send money home. These clubs didn’t just preserve culture-they built survival networks.