What Are the Disadvantages of a Charitable Remainder Trust?

Nov, 21 2025

Nov, 21 2025

CRT Suitability Calculator

Assess Your Charitable Remainder Trust Suitability

Your Suitability Assessment

Key Considerations

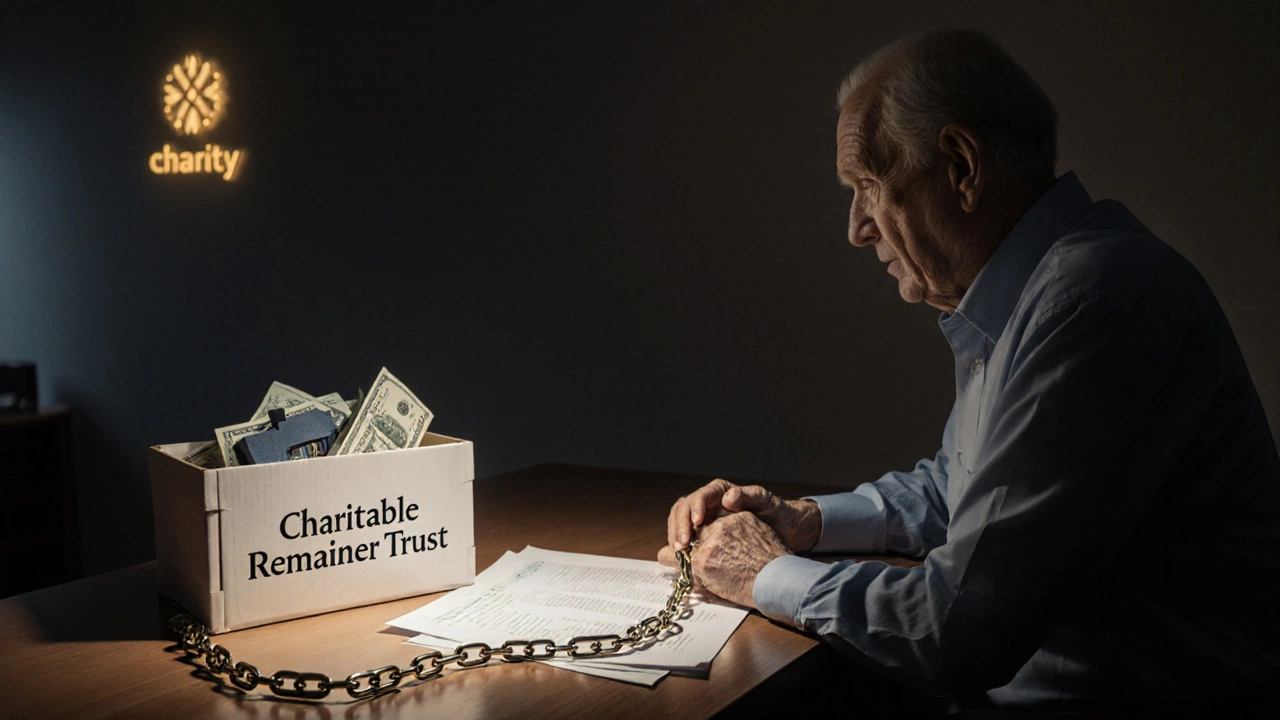

People often hear about charitable remainder trusts as a smart way to give to charity while keeping income for yourself. And sure, they can be powerful tools - but they’re not perfect. Before you set one up, you need to know what you’re giving up. There are hidden costs, rigid rules, and situations where this kind of trust does more harm than good.

You lose control over the assets

Once you put assets into a charitable remainder trust, they’re no longer yours. Not really. You can’t sell them, move them, or change your mind later. Even if your financial situation changes - say, you lose your job, get sick, or need cash for an emergency - you can’t take the money back. The trust is irrevocable by law. That means you’re locking up property, stocks, or real estate for decades, with no way out. For many, that’s a risk they didn’t expect to take.

The income isn’t guaranteed

Charitable remainder trusts pay you (or someone you name) an income for life or a set number of years. But here’s the catch: that income depends on how the trust’s investments perform. If the market drops, your payments shrink. If the trust holds volatile assets like private equity or rental property, your income can swing wildly from year to year. There’s no safety net. Unlike an annuity or a pension, you can’t count on steady checks. One study from the National Center for Charitable Statistics found that nearly 30% of CRTs paid less than 4% annually in their first five years due to poor investment returns.

It’s expensive to set up and run

Setting up a charitable remainder trust isn’t like writing a will. You need an attorney who knows estate law, a trustee to manage the assets, and an accountant to handle tax filings. Initial setup costs can run $5,000 to $15,000. Then there are annual fees - trustees charge 1% to 2% of the trust’s value each year. So if your trust holds $500,000, you’re paying $5,000 to $10,000 just to keep it running. Over 20 years, that’s $100,000 in fees. That money could’ve gone to the charity - or to your family.

You pay taxes on the income you receive

Here’s a myth: people think CRT income is tax-free. It’s not. The IRS treats distributions in a specific order: first ordinary income, then capital gains, then tax-free return of principal, and finally tax-free charity. Most of the early payments are taxed as ordinary income - which could push you into a higher tax bracket. If you’re in your 70s and pulling $30,000 a year from the trust, you might owe $6,000 or more in federal taxes alone. That eats into your income fast. And if the trust sells appreciated assets (like stock you bought for $10,000 that’s now worth $100,000), you still owe capital gains tax on the portion paid out to you.

The charity gets everything - eventually

At the end of the trust term, the remaining assets go to the charity. That’s the whole point. But what if your kids or grandchildren need that money? What if the charity changes its mission? What if the organization you chose closes down? You have no say. Even if your children are struggling with medical bills or student debt, the trust can’t help them. It’s locked in. And if the charity goes bankrupt, the court may redirect the assets to another nonprofit - one you never chose.

You can’t easily change the charity

When you create the trust, you pick one or more charities. That’s it. You can’t switch later, even if your favorite nonprofit shuts down or starts doing things you disagree with. You’re stuck with the charity you chose 10, 20, or 30 years ago. Many people don’t realize how much charities change over time. A local food bank today might become a national advocacy group tomorrow. If you cared about helping homeless veterans, but the trust ends up funding climate research, you have no power to stop it.

It doesn’t work well with small estates

Charitable remainder trusts are designed for people with significant assets - usually over $500,000. If you have less, the fees and complexity just don’t make sense. For example, if you put $200,000 into a CRT and pay $10,000 a year in fees, you’re losing 5% of your principal just to keep it alive. Meanwhile, a simple donor-advised fund costs under $1,000 to set up and lets you give to multiple charities over time. You keep control. You get tax deductions. You don’t lock up your money. For most middle-income givers, a CRT is overkill.

It can hurt your family’s inheritance

Let’s say you have two children. You set up a CRT with $800,000 in stocks. You get 5% income ($40,000/year) for life. After you die, the remaining $600,000 goes to a museum. Your kids get nothing. But if you’d just sold the stocks, paid the capital gains tax once ($120,000), and left the rest to them, they’d have $680,000. The CRT didn’t help them - it took their inheritance. And if you die young, they get even less. The trust doesn’t care about your family’s needs. It only cares about the charity’s future.

It’s hard to find good trustees

Who manages your trust? You need someone trustworthy, experienced, and willing to take on legal responsibility. Banks and law firms charge high fees. Friends or family members? They might not know how to handle investments, file tax returns, or deal with beneficiaries. If the trustee makes a mistake - say, they invest too aggressively or miss a tax deadline - you’re on the hook. The IRS can penalize the trust. Your income could be cut. The charity might sue. And you can’t just fire them. Replacing a trustee in a CRT is a legal nightmare.

You’re better off with simpler options

There are easier, cheaper ways to give to charity and still get tax breaks. A donor-advised fund lets you donate cash or stock now, get an immediate tax deduction, and recommend grants to charities over time. You can change charities anytime. You can add money. You can pause giving. Fees are low - often under $100 a year. Or you could leave a bequest in your will. No setup cost. No annual fees. No loss of control. You can even name multiple charities. And if your situation changes, you update your will - no court involved.

Charitable remainder trusts aren’t bad. But they’re not for everyone. They’re complex, expensive, and inflexible. If you’re wealthy, have long-term goals, and want to support a specific charity for decades, they might make sense. But if you’re looking for a simple way to give, protect your family, or avoid paperwork - skip it. There are better paths.

Can I change the charity in my charitable remainder trust later?

No, you cannot change the charity once the trust is created. The charity is named in the trust document and locked in permanently. Even if the organization changes its mission, closes, or you lose trust in it, the law doesn’t allow you to redirect the assets. That’s why choosing the right charity upfront is critical.

Is the income from a charitable remainder trust tax-free?

No, the income is not tax-free. The IRS taxes distributions in a specific order: first as ordinary income (like interest or dividends), then as capital gains, then as tax-free return of principal, and finally as tax-free charitable remainder. Most recipients pay taxes on the first portion, which can be substantial - especially if the trust sold appreciated assets.

How much money do I need to make a charitable remainder trust worthwhile?

Generally, you need at least $500,000 in assets to make a charitable remainder trust cost-effective. Below that, the setup and annual fees (often $5,000-$15,000 initially, plus 1%-2% yearly) eat into your returns faster than the tax benefits help. For smaller estates, donor-advised funds or bequests are simpler and cheaper.

What happens if I die early after setting up the trust?

If you die early, your income payments stop. The remaining assets go to the charity, even if you only received a few years of payments. Your heirs get nothing from the trust. That’s a major risk - especially if you’re younger or in poor health. The trust doesn’t protect your family’s financial future.

Can I use real estate in a charitable remainder trust?

Yes, you can put real estate into a charitable remainder trust, but it’s complicated. The trustee must manage the property, pay taxes, insurance, and maintenance. If the property doesn’t generate income, your payments may be low or delayed. Selling it later can trigger capital gains tax on the portion paid to you. Many advisors recommend cash or stocks instead for simplicity.

Are there alternatives to a charitable remainder trust?

Yes. Donor-advised funds let you donate now, get an immediate tax deduction, and recommend grants over time - with no setup fees beyond the fund’s minimum. You can change charities, add money, and stop giving anytime. Bequests in your will let you leave money to charity after you die, with no ongoing costs. Both options give you control and flexibility without the rigidity of a CRT.

Who should NOT consider a charitable remainder trust?

Anyone who needs access to their assets, has an estate under $500,000, wants to leave money to family, or values flexibility should avoid it. Also avoid it if you’re unsure about your chosen charity, have health concerns, or want to support multiple causes. Simpler tools like donor-advised funds or wills are better fits.